Elli Smula was born in Charlottenburg near Berlin on 10 October 1914, shortly after the beginning of the First World War. At the time, her mother, Martha Smula, worked as a housemaid in Hohenlychen in Uckermark (about 100 km north of Berlin) – presumably at a local sanatorium for women and children with pulmonary diseases.

Martha Smula was born in Brieg/Oder (Lower Silesia, what is Brzeg/Poland today), a town 40 km southeast of Breslau, in 1892. She came from a modest background and started to work as a maid at the age of 14. Martha Smula was Protestant.

In 1911 her son Willi was born, three years later her daughter Elli (the given name is occasionally also spelled Elly). The children’s father died as a soldier during WWI. Since Elli’s parents had not been married, Martha Smula did not receive any widow’s pension and had to earn a living for herself and the children on her own.

Later on, the family moved from Hohenlychen to Berlin. One of Martha Smula’s sisters was living there and probably also some other family members. Starting from 1937, Martha Smula is listed in Berlin address books as employed by an innkeeper at 92, Blumenstraße in the Mitte district. She and her daughter lived on the fourth floor of the side wing.

Elli Smula was an unskilled worker. Most likely there was no money left for her professional training after her brother Willi’s apprenticeship as a carpenter. Perhaps she went to the “Resi Casino” now and then – a notorious Berlin café with a dance floor located at 10, Blumenstraße, across the street from her apartment building. “Resi” offered dance music with a large orchestra and had all kinds of fancy modern amenities like table telephones, pipe-mail in the ballroom, water fountains, and light shows.

We do not know if Elli Smula had a boyfriend or a girlfriend. There are no personal documents (such as letters, for example), which would allow us to draw conclusions about her private life. She was unmarried, and – as far as is known – she was not a member of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP) or any other party organization like the League of German Girls (BDM) or the National Socialist Women’s League.

In the summer of 1940, Elli Smula – who was 25 years old at the time – was mobilized to work for the Berlin Transport Company (BVG). The BVG had to carry thousands of passengers to their workplace in the armaments industry every day. Since many of its manual workers and employees were drafted into the army, the BVG suffered a severe personnel shortage. Consequently, more than 3 000 women were used to fill those posts. They even worked as conductors – a job that had been reserved for men so far.

Elli Smula started her employment at BVG in the Berlin district of Treptow on 23 July 1940. She was appointed conductor at the train service of the tram depot Elsenstraße, the starting and end point of a number of tramlines. On the very same day Margarete Rosenberg also started to work there. The 30-year-old woman, who had no professional training either, had worked as a prostitute for a few of the preceding years. She had been subjected to various official harrassments regarding prostitutes – that is, she had had to regularly pass STD-tests at the public health authority. In 1935, Margarete Rosenberg had gotten married to a former suitor.

A few weeks after their commencement of duties, both women were detained by the Secret State Police (Gestapo) – Elli Smula on 12 September 1940 at work and Margarete Rosenberg three days later – and taken to the police prison at Alexanderplatz.

Over the following weeks, they were taken from the police headquarters to 8, Prinz-Albrecht-Straße at least four times, where they were separately interrogated. This address had been the seat of the Gestapo headquarters since 1933 and, since 1939, also that of the Reich Main Security Office, which coordinated the Europe-wide network of police and SS. It was synonymous with terror.

The investigation was conducted by the Gestapo-Office IV B 1 c. In the year 1940, this code designated the section “homosexuality”, which was part of the unit for “party affairs, oppositional juveniles, and particular cases”. It was detective inspector Friedrich Fehling who was chiefly in charge of combating homosexuality at the secret state police authorities. He did so from 1934 until the end of the war, with some interruptions.

Although for the main part it was the criminal investigation department that was in charge of the prosecution of homosexual men since the beginning of the war, the Gestapo’s homosexuality-department also continued to operate. The historian Andreas Pretzel discovered that in 1940, the Gestapo investigated approximately 150 men suspected of homosexuality in Berlin alone. It is a little known fact that this office also investigated women suspected of lesbian relations.

What Elli Smula and Margarete Rosenberg were accused of can be gathered from a note by the Gestapo-Office IV B 1 c, 26 September 1940. It states that:

The BVG received complaints that some female conductors who served in the tram station Treptow maintained regular intercourse with fellow women workers of their station – lesbian intercourse, that is. For instance, it was asserted that they took fellow workers with them back to their place, plied them with alcohol, and then performed homosexual intercourse with them. The next day, the women were consequently not able to carry out their duties. As a result, the operation of the tram station Treptow was severely compromised.

The BVG made a report to the Gestapo, whereupon a detailed investigation was ordered. We do not know who betrayed Elli Smula and Margarete Rosenberg. Was it a female colleague or a supervisor? The BVG, which had been on its way to turning into a “National Socialist model plant” since 1933, had already set up a “security service” that same year to intimidate staff, throwing the doors wide open for denunciations.

Margarete Rosenberg eventually confessed to “having taken part in drinking parties and having had homosexual intercourse with women”. The Gestapo concluded that, as a result of her “unsound moral conduct”, she had not carried out her duties in a regular manner. Was the confession true? Had it come about through torture? It has to be assumed that in the course of the investigation other tram conductors and other colleagues were questioned on this matter. There are no names or records of interrogation passed down, however.

Sexual acts between women, in contrast to those between men, did not fall under article 175 of the criminal code and for that reason the Gestapo could not hand the “case” over for prosecution . But apparently, merely closing the investigation was not an option either. The Gestapo imposed preventive detention instead – which meant the transfer to a concentration camp without prospect of release. An appeal against this decision was not possible.

Elli Smula was interrogated on 10 October 1940, her 26th birthday, for the last time. She still spent the following weeks in the police prison at Alexanderplatz. She was allowed to see her mother there once, under supervision. Apparently she suffered from hunger. Elli Smula and Margarete Rosenberg were deported to the concentration camp Ravensbrück on 30 November 1940, and – together with 56 other women – they were registered as “new entrants” there. Margarete Rosenberg’s warrant of arrest indicated “subversive conduct” and this was presumably also the case for Elli Smula. Both were assigned to the Political Detainees, which meant that they had to wear a red triangle in the camp.

The arrivals list of the concentration camp Ravensbrück shows the additional note “lesbian” for both, right next to the grounds for detention (political). When Margarete Rosenberg was transferred to another camp in January 1945, this record traveled with her. She survived the more than 4-year-period of detention with serious damage to her health and died in 1985.

When Elli Smula, like other detainees, was allowed to write a few lines to her mother and receive letters from her respectively, this mail was subject to strict censorship. In July 1943, Martha Smula received a notice from Ravensbrück’s camp administration that informed her of the “very sudden” death of her daughter on 8 July 1943. Elli Smula was 28 years old at that time. Did she die of hunger or exhaustion? Or of some disease due to the poor sanitary conditions at the blocks, which were completely overcrowded in 1943?

Elli Smula and Margarete Rosenberg were detained after being charged with “severly compromising the operation of the tram station Treptow”. Even though lesbian acts did not fall under article 175, they undoubtedly violated moral norms – even more so within a strategic business like the BVG, as a lot of things in the capital of the Reich depended on the smooth operation of public transportation.

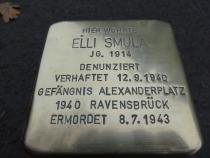

Elli Smula

Location

gegenüber Singerstraße 120

Historical name

Blumenstraße 92

District

Mitte

Stone was laid

16 November 2015

Born

10 October 1914 in Berlin-Charlottenburg

Occupation

Arbeiterin

Verhaftet

12 September 1940 to 30 November 1940

in

Polizeigefängnis Alexanderplatz

Deportation

on 30 November 1940

to

KZ Ravensbrück

Murdered

08 July 1943 im KZ Ravensbrück